In pursuing these questions, we undertook 1) literary analysis of archival documents describing the limits of humanitarian language for conceiving of refugees; 2) historical research into the ways in which governments and prewar agencies made sense of forced displacement in the context of protracted crisis in the Levant; 3) philological study of how the rich and textured root structure of the Arabic language inspired a set of indigenous terms in Arab-Islamic history, which were used to describe forced displacement; 4) interviews with displaced people living in Jordan to better understand how these indigenous terms still operate today beyond the lexicon of policy.

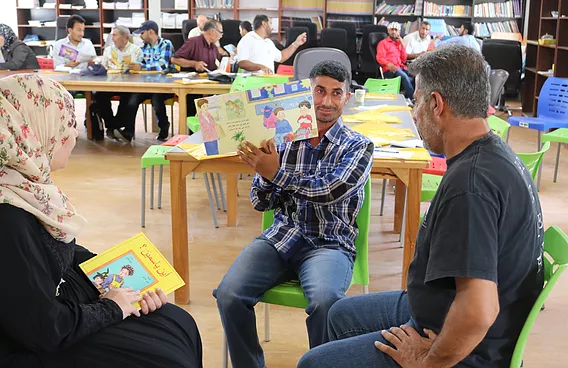

By better understanding the historically-mediated and indigenous forms through which displaced people have conceived themselves in the region, and subsequently disseminating our findings through the lexicon of policy, we challenged the bureaucratic institutions tasked with regulating humanitarian aid – including governments, INGOS, and UN agencies. In turn, local communities and researchers were at the heart of the project’s undertaking, both in terms of its initial design and the direction it has taken. As the project aimed towards deriving forms of agency from within local communities and their inherited linguistic terms, we prioritized their involvement at all stages, including training local research assistants and translators.